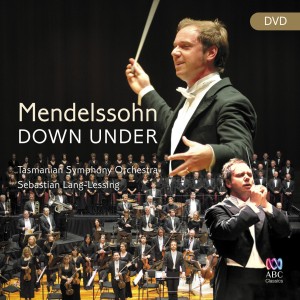

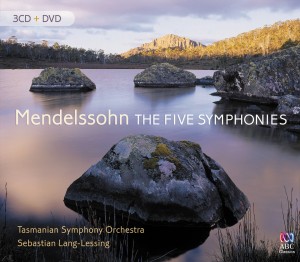

Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra

Sebastian Lang-Lessing (conductor)

ABC Classics 476 4623 (3CDs + DVD)

TPT: 128’ 52”

reviewed by Neville Cohn

Last year, when the world was awash with performances of the music of Mendelssohn to mark the bicentenary of the composer’s birth in 1809, many regular concertgoers who thought they had a good overview of his music, found themselves on an often gratifying journey of discovery. This applied particularly to his chamber music, the complete string quartets, say, which for many might well have proved revelatory.

As far as the symphonies are concerned, most concertgoers would readily be able to identify the works dubbed Scottish and Italian. They are frequently performed and with good reason. And mini-polls I’ve conducted in the foyers of this or that concert venue around the city reveal clearly that, frequently, even the keenest of music followers have only the vaguest ideas about the existence of Mendelssohn’s other symphonic utterances apart from the ubiquitous Third and Fourth.

Bear in mind, too, that by the time Mendelssohn got round to composing what we know now as his Symphony No 1, he had been at work in the genre for much of his adolescence, producing a stream of so-called string symphonies. Many of these are astonishingly original without a hint that they’d been written by a teenager.

This 3-CD + DVD set will, I believe, bring many new adherents to the flag, not least for providing an opportunity to hear works that only very rarely appear on concert programmes these days.

Listen to Sebastian Lang-Lessing’s direction of the Tasmania Symphony Orchestra in Mendelssohn’s Symphony No 1. How splendidly this fine ensemble evokes the ebullience of the first movement. It’s a performance which brims with energy, again and again carrying the listener forward on the crest of a finely stated orchestral wave. Lang-Lessing and the TSO are no less persuasive in the second movement; its gentle, lyrical calm makes it a near-perfect foil for the energetic bustle that precedes it.

In the Minuetto, Mendelssohn’s usually sure touch is less apparent; it is overly bucolic music and the Trio excessively solemn and serious. But the finale is inspired as is its performance, not least for excellent clarinet playing and precise pizzicato which add significantly to the engaging bustle of the music.

The Scottish Symphony is in a class of its own. How intriguing that a German could identify so profoundly with Scotland based on the briefest of visits to that part of the world. (Consider, too, the quite magically atmospheric Fingal’s Cave Overture. When will some musical Scot turn out a couple of masterpieces after some brief encounter with Germany? Don’t hold your breath!)

Lang-Lessing makes magic of the first movement. Clarinet playing in the Vivace non troppo is beyond reproach in a movement that is as Scottish as a tartan kilt and sporran.

A shrewd commentator once described the finale as “a wild dance of rude Highlanders who stamp furiously into a smug coda………”. And who would gainsay that view on the basis of this splendidly bracing account?

Almost invariably, when Mendelssohn visited England, there’d be an invitation to Buckingham Palace. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were great admirers of the famed composer – and Victoria would, shyly, sing some of the lieder by “dear Dr Mendelssohn” with the composer accompanying at the piano. And when the composer asked if he might dedicate his Scottish Symphony to her, she agreed at once. Victoria would often attend public performances of Mendelssohn’s music which invariably ensured full houses.

Inspiration informs just about every moment of this account of the Italian Symphony with Lang-Lessing and the TSO coming through with honour not only intact but enhanced. There’s not a dull moment here. The quick movements crackle with energy, the opening allegro vivace splendidly precise at top speed as is the ever-engaging Saltarello. Intriguingly, this exquisite movement, which sounds as if it might have been conceived in a single, sustained burst of highest inspiration, never quite satisfied the composer who seriously considered revising it. Happily, he didn’t; it comes as close to perfection as anything he ever wrote.

But not even the skill and commitment of the players can persuade this listener that the first movement of the Reformation Symphony is other than ponderously dull and the allegro vivace that follows amiable but unremarkable. Mendelssohn’s inspiration was no less in short supply in the pompous, lacklustre finale. But that certainly does not lessen the importance of including it – and the dreary and overlong Lobgesang – in this important recording enterprise.

It says a great deal for the skill and commitment of both conductor and orchestra that, for the duration of Lobgeasang and the Reformation symphony, these works sound far better than they in fact are.