The Man from Mukinupin

New Fortune Theatre, UWA

reviewed by Neville Cohn

For those who look forward to GRADS’ Shakespearean offerings on UWA campus, there are only the leanest pickings from the Bard for 2013 – a few moments from Othello presented as a play within a play in Dorothy Hewett’s The Man from Mukinupin.

Peopled by a range of often-odd citizens who live in Hewett’s imaginary town in the back blocks of W.A., the play makes for an absorbing theatre experience. And it says a great deal for director Aarne Neeme and his large cast, that momentum was so efficiently maintained in a play that, unless carefully managed, can all too easily die of inertia. Not so here. It unfolded beautifully. It hadn’t a dull moment.

Above the Mukinupin council chambers at stage rear were positioned a number of musicians who did sterling work in both mood evocation and backing of vocals, although overly repetitive keyboard figurations in music prior to the play proper were an essay in dullness.

Small country towns, just as big cities, invariably have their share of inhabitants who’ve experienced disappointment and deprivation. And who more so than Clemmy (played by Yvette Wall), a former circus tightrope walker – a small star but a star nonetheless – who survives a fall that has crippled her. She gets about with a crutch and limps badly. Her manner cleverly evoked an aura of past glory, regret tinged by despair.

Cameron Taylor was altogether impressive as Jack, the young grocery shop assistant clearly deeply enamoured of his boss’ daughter. When World War I breaks out, he joins up with all the enthusiasm of a young patriot doing his duty without, perhaps, the realisation of what really lies before him and so many of his generation.

As Jack’s love interest, Polly, Bonnie Coyle was entirely convincing. With the fresh-faced innocence of youth, she made of Polly a delightful personality.

Hewett calls for a large cast and some not only double up but triple up as does Kenneth Gasmier who delighted as a fussy cum pompous travelling salesman on the lookout for domestic bliss. He has an eye on Polly. He’s also an orange-robed Othello in a tiny travelling theatre troop as well as – quel horreur! – a flasher in trade-mark raincoat and very little else.

No less convincing was Rosemary Longhurst who seemed positively to relish her twin roles as Clarry and black-garbed widow Tuesday. Peter Fry, too, was beyond reproach as shopkeeper Eek – and his alter ego Zeek. And Liz Hoffmann came up trumps as Eek’s wife Edie, ear-trumpet and all.

As is often the case in remote places, gossip is a currency sometimes valued greater than gold and there’s a good deal of it, spoken in low voices, in Mukinupin – and Hewett’s touch here is faultless, her lines again and again having the stamp of sometimes uncomfortable truth.

If this production of The Man from Mukinupin is anything to go by, GRADS are likely to have a very good year.

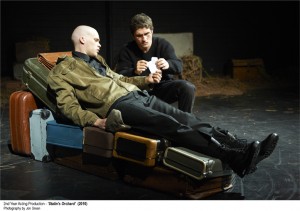

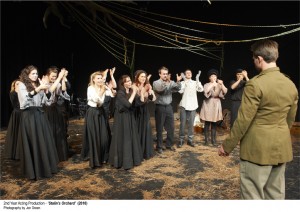

Photos by Merri Ford and Maddy Connellan