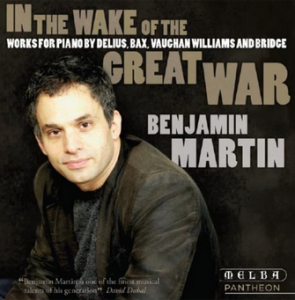

Benjamin Martin, piano

MELBA

TTP: 62’ 08”

reviewed by Neville Cohn

Understandably, in this centenary year of the outbreak of World War I, there’s been a flood of recordings of music influenced by this terrible and protracted upheaval.

Pianist Benjamin Martin recently recorded a number of works for piano written in the early aftermath of this conflict.

Arnold Bax’s Third Sonata in G sharp minor is of particular interest. It came into being at a troubled time for the composer, his immediate family – and two women with whom he was having affairs. While hardly anyone these days cares tuppence whether people living together are married or not, in the 1920s cohabitation was considered scandalous and talked about in low voices.

Of Bax’s two mistresses, Harriet Cohen and Mary Gleaves, it was Cohen who was by far the most famous – perhaps notorious is the better word. Miss Cohen, in fact, had an affair as well with Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and extremely close relationships with other eminent Establishment figures.

Bax was Master of the King’s Musick – and uncharitable types would often snidely refer to Miss Cohen as Mistress of the King’s Musick. For years, Cohen was Bax’s muse, inspiring him to write many a work which might otherwise have not eventuated. The Sonata No 3 is in that category.

Its outer movements are turbulent and often confrontational, a response perhaps to the domestic quagmire Bax found himself in at the time, with much internecine warfare on the marriage front. Mrs Bax flatly refused to give her husband the divorce he wanted. And because of puritanical attitudes at the time, the Bax/Cohen liaison had to be conducted in furtive ways. The Sonata is dedicated to Cohen.

The first movement comes across as an extended improvisation, with mercurial sallies and bursts of energy that call to mind some of Scriabin’s busier piano preludes. There are also fleeting moments of tenderness. In less assured hands, this could all too easily come across as aimless, rambling, turgid and tedious. But Martin, with fearless fingers, steers a sure course through a musical minefield without coming to grief.

Martin sounds in his element in the slow movement which comes across as a murmuring, introverted sonic haze, like a peaceful nocturne – a calm harbour after stormy seas. And in the finale, Martin sails with elan and accuracy through a floodtide of notes.

Vaughan Williams’ Hymn-tune Prelude, also dedicated to Cohen, is an oasis of tranquillity, unhurried and beautifully considered, reinforcing that old saying that the best gifts often come in the smallest packages. It certainly applies here.

Three Preludes by Delius are frankly ephemeral, miniatures not without a certain faded charm, especially when presented with such insight as here.

Frank Bridge taught Benjamin Britten as a child and, in gratitude, Britten later wrote his Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge thus ensuring the older man a lasting celebrity which his own music might not.

All praise to Benjamin Martin for taking us across Bridge’s musical terrain with such authority – but not even this fine pianist can bring a sense of meaning to a veritable tsunami of notes. Handwringing anguish, moments of nocturnal tranquillity, bunched chords, moments of ominous confrontation, filigree coruscations, deep bass rumblings – there’s no shortage of ideas. But just as preparing a cake using fine ingredients is not enough to ensure an appetising outcome unless the flour, sugar, baking powder are brought together in a way that ensures success, so mixing often worthwhile musical ideas without a carefully thought-through strategy, can result in disappointment – a musical cake fallen flat.

Here, Bridge throws into the mix villainously difficult filigree coruscations,

dreamy nocturnal moments, emphatic bunched chords, quiet bass rumblings. But despite these being handled with the skill and staying power of an Olympic athlete, one is left with an impression of a succession of ideas (many impressive and engaging) that calls to mind a number of articulate people busily talking but without listening to one another.