Chris Edmund (director)

Enright Studio (W.A.Academy of Performing Arts)

reviewed by Neville Cohn

Yet again, Chris Edmund has demonstrated impressively and unambiguously that, in theatrical terms, he is a master when it comes to the evocation of political terror. The prime focus here is two men with almost limitless political power and who, in different ways, have callously misruled over a great people.

According to the printed program, Stalin’s Orchard is written by Edmund in collaboration with the cast but throughout its compulsively watchable duration Edmund’s near-flawless directorial touch is everywhere apparent.

Alas, the hoped for amelioration of the Russian people’s plight after decades of hideously cruel rule by Stalin and those who came after him until the rise of Gorbachev brought some hope to a cowed population, has not eventuated to any significant degree. Now, another cynical and ruthless politician presides over the nation with an ever-tightening hold on the Russian people who react to the current dispensation, as ever, with stoicism.

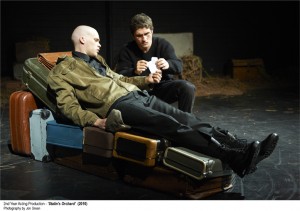

Stalin’s Orchard is a 90-minute-long, compulsively watchable series of vignettes, almost each one of which has the vivid stamp of truth. Here we watch as Stalin, that arch-cynic and mass murderer of his own people, demonstrates his appalling and complete power over the very existence of the people he rules with ruthless disregard for the civilised norms we take for granted. And the rot that has set in under Vladimir Putin is demonstrated in numbers of ways but especially in the white slave trade that enriches the few and humiliates and debases too many of the defenceless weak.

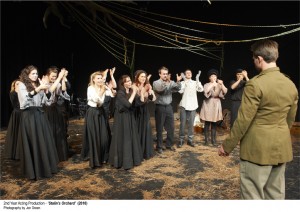

Young in years the cast may be, but each brief scene makes its point in a striking way – and this would be largely due to Edmund’s faultless directorial touch. There are many very ugly truths in this production in a play that brings us face to face, as it were, with the terrible dilemmas that are routinely the fate of just about every Russian citizen except for those given official protection and who get away, quite literally, with murder if it suits their callous requirements.

Throughout, three crones – on stilts! – give a cackling commentary. Were these offered as a type of homage to the three witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth?

The only reservation was the decibel levels of Stalin’s voice which sounded uncharacteristically loud. Unlike those who came before him, for instance Lenin, whose oratorical style involved a great deal of shouting cum hectoring with extravagant arm waving and fist pounding, Stalin made a conscious decision to always talk softly in public or in broadcasts to his cowed people.

Despite the need for frequent, very rapid costume changes, the play came across with unflagging onward momentum. There wasn’t a dull moment; it was, in fact, consistently fascinating. The players are young – they are all 2nd year acting students – yet they confidently handle what would be a very great theatrical challenge. Bravo!.

Stalin’s Orchard deserves an international audience.