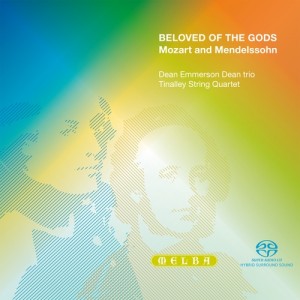

Dean Emmerson Dean Trio

Tinalley String Quartet

TPT: 68’08”

Melba MR301121

reviewed by Neville Cohn

Kegelstatt Trio (Mozart)

Papamina Suite (Mozart arranged Emmerson)

Quartet in A minor op 13 (Mendelssohn)

Around the world, innumerable recitals and concerts have marked the bicentenary of Felix Mendelssohn’s birth in 1809.

Earlier this year at the Perth International Arts Festival, his complete string quartets were programmed. For many, perhaps most, of those who attended these performances, it was a musical journey of discovery that brought home emphatically that there is so very much more to Mendelssohn than some of his sentimental Songs without Words, elfin-type essays of one type or another, the hackneyed Wedding March and, of course, the ubiquitous – and exquisite – Violin Concerto in E minor.

Played by the Tinalley String Quartet, Mendelssohn’s opus 13 in A minor makes compelling listening. The opening adagio – allegro vivace is given a model reading in which the composer’s musical argument is expounded in sometimes achingly beautiful terms.

Crown of this recording is the Intermezzo, a haunting little dance episode that is the quintessence of sadness that bring to mind those heartbreaking moments immediately after Rigoletto discovers that his daughter Gilda has been kidnapped; it’s a brief interlude of despair beyond despair. Here, the Tinalley musicians take up an interpretative position at the emotional epicentre of the music. In a finale that rivets the attention, the players, after a brief obeisance to the opening moments of the closing movement of of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, respond to the score in an intensely dramatic way.

Recording engineers: step forward and take a bow for your skill in magically capturing a performance of Mozart’s engaging Kegelstatt Trio on disc. It doesn’t happen very often that there is such fidelity in a recording that it sounds as if the performance is taking place ‘live’ in your lounge or wherever you happen to be listening. It is a joy to hear – and, happily, the performance is on a par with that. So, too, does Stephen Emmerson’s arrangement for the same instrumentation – Brett Dean (viola), Paul Dean (clarinet), Stephen Emmerson (piano) – of a suite drawn from Mozart’s The Magic Flute. It’s a recorded performance of great distinction. It’s a finely managed oscillation between good humour and deep emotion, a model of its kind that deserves to be heard by many. Bravo!

Neither of the composers represented on this disc saw their fortieth birthday. Imagine what riches the world was deprived of by their tragically early demise. Imagine, too, what might have issued from Mozart’s pen had he lived another year – another month! The same could be said of Mendelssohn.